"This shit wold be way easier if the world would just hurry up and fall apart."

That was the thought that jumped into my thoughts as I was rummaging through hand-written scribbles from a few years back. ChatGPT wasn't being especially helpful in synthesizing the thirty-eight divergent ideas I fed it. The best idea my AI sidekick could generate was a hybrid between Jim Jones' People's Temple Agricultural Project (of "Drink the Kool-aid" fame) and Scientology.

FML.

You see, for the last fifteen years or so, I've been fascinated with the social dynamics of self-improvement. Specifically, how do groups positively influence people's journey to self-improvement.

Part of the fascination has been fueled by evidence... I have a whole lotta anecdotal (and empirical) evidence that surrounding yourself with hard-working, motivated people super-charges your own self-improvement. The friendly competition and accountability is helpful, too.

Another part of the fascination is fueled by a strong desire for authentic connection with others, and the sense of belonging to a group of like-minded folks. Our modern world is a lonely, isolated place. Since the dawn of time (for humans, anyway), we've relied on a tribe of other people to survive. "Lone wolves" didn't last long in the harsh, unforgiving wilds of our primal past. Given each of us is the result of a long, unbroken chain of social animals, tribalism is etched into our DNA. Hell, the entire field of "social psychology" is dedicated to studying our innate social acumen.

Anyway, this fascination with the social dynamics of self-improvement have led to the formation of a fairly long series of intentional and unintentional "tribes" I've either started or became a part of. Some have been centered around a particular activity, like the Runner's World Barefoot Running Forum, The Barefoot Runner's Society, BRU, The Hobby Joggas, BRUCrew, Fight Club, and El Diablo Combatives. Others have been centered around ideas, like Families on the Road and Cotton Underwear Nougat Troupe. Still others were specific to self-improvement, including Man Camp and The Lab. Some were really successful. Some weren't.

Each idea provided some insight on what works and what doesn't work; each idea has been a step towards solving a riddle... a riddle that would be wayyyy easier to solve if we had some external force that would force us to have to need each other.

Like the apocalypse.

But alas, we have to work with the world we have, not the world we want.

I. The Goal

The ultimate goal is to surround myself with a "gang" other men who have a strong desire to improve themselves in a variety of fun, exciting, and adventurous ways, have a strong sense of duty to provide and protect their families and communities, and also crave the camaraderie and brotherhood of other men who are striving for the same. Every member would bring their own contributions to the group by teaching what they know and learning what they don't. The men would set goals and hold each other accountable for accomplishing those goals. My specific contribution would be teaching a lot of the stuff that I've written about in this blog and others, like sleep and heath, physical fitness and diet, ethics and values, social skills, sex and romantic relationships, and personal growth. Basically, can teach men how to be better at being men.

The most successful incarnation of this idea is the Man Camp, which this blog (and its grittier, more offensive predecessor), was really good. But it had two fatal flaws. First, it was mostly online. Second, it was designed to solve a specific problem (fixing "Nice Guys"), not to develop a particular type of man to be a better version of themselves. I'll elaborate on this point more, later.

It's worth noting, for readers who are unfamiliar with my ideas, that the idea of a men's only group is intentional and based on the science of gender in general and evolutionary psychology and biology in particular. The exact explanation of the rationale goes beyond the scope of this post, but if you really want to understand why we exclude women, you can read this post:

The Science and Logic Behind Our Philosophy: A Discussion on Feminism, Masculinity, and the Patriarchy

My hypothetical Gang of Men is still solving a problem, but it's a far more generalized problem than the Nice Guy issue.

II. The Problem We're Solving

Simply put, our modern society makes men soft, and modern society keeps us isolated. This isn't some conspiratorial plot hatched by evil masterminds in an underground lair; it's merely the natural cause and effect of progress and technology. We know this because we've seen this story before. Many, many times before.

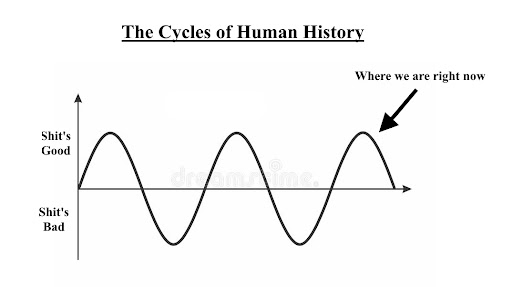

Human history is cyclical. If we want to predict the future, all we have to do is look at the past. And any objective study of the past strongly suggests we're currently just creeping past the apex in our current cycle. It looks something like this:

Every society in recorded history prior to the modern day, and those before recorded history, have followed the same rise -> peak -> collapse pattern. EVERY one. And every one of those societies believed they would be the exception to that rule. They believed they would be too good to fail. And they were wrong.

The cycle works like this:

1. Motivated, hard-working people bust their asses to improve their society, usually through development and technological innovation. Early in our history, this involved inventions like the harnessing of fire, the smelting of bronze, and the wheel. In more modern times, this has included cell phones, traction control, and Door Dash.

2. As the standard of living increases and life gets easier, more and more humans get lazy. And complacent. As the struggle to survive wanes, we start occupying our time with other pursuits and forget all the skills that we needed to survive before our society reached its apex. In other words, we get soft. We also start engaging in behaviors that sabotage our society by destroying the social fabric that holds the society together. Specifically, we see a precipitous decline in moral values, political corruption, automation of basic tasks, economic instability caused by greed, and a loss of a sense of identity. We tend to start believing in ideologies that divide us in ways that assure we start viewing our fellow community members as enemies, which threatens to tear our society apart.

3. An event or a confluence of events create a tipping point where the strained society snaps because the society has lost the ability to work together to overcome adversity. The society endures a rapid decline in the standard of living. This rapid decline occurs because too many people within the society have lost the skills and resiliency needed to survive real hardships. This is typically a time of great pain and suffering, death and destruction. Chaos and war are common. I like to call this process "The Voiding" because it's as if all of our progress is simply voided out. SOME people in the society do just fine; for various reasons they maintained the skills and resiliency needed to survive. These survivors either band together to form functional, successful communities OR become what amounts to despots and warlords.

4. Over time, those who organized as successful communities overcome the terror of the despots and start building a new society. And the cycle begins anew.

I believe we're currently past the apex, which probably happened around the late 90's up to 9/11. Since that time, our society has been rapidly ripping itself apart. For me, the test to determine where we are in that cycle of human history was COVID. It was a major issue; to date about 7 million people have died from the disease. The economic impact has been calculated to about a 4% decrease in global GDP... which is about as bad as The Great Depression. The key, though, isn't the degree of the pandemic. It's our response to the pandemic.

If we had a functional society, humanity would have come together to face the problem. That clearly did not happen. In fact, I'd bet a large sum of money that every person who reads this had a spike in their blood pressure as soon as I mentioned COVID because it triggered some emotional response that is caused by the divisions within our society. We're past the tipping point; we're in The Voiding.

The problem is the last few decades have made men weak and isolated, which has destroyed our ability to be resilient in the face of adversity. Take the average American man today and plop him out in the wilderness with nothing. He would be dead within three days, assuming it wasn't too cold or too hot.

I won't go into detail here about all of the qualities of modern American men that make them weak as fuck, because men who get it, get it. Men who don't, get pissy and defensive. I'm not interested in speaking to the "pissy and defensive" men; they're not the men who have that drive to provide, protect, and really put in the hard work to become the best version of themselves. They're not the men I want in my Gang.

Before I get into the specifics, I have to discuss what went wrong with the previous groups I've associated with over the years.

III. The Issues with the Previous Social Groups

Some of these groups were successful, especially for their intended purpose. Others were abysmal failures. But none really accomplished my overall goal of achieving my "Utopia" Gang. Here's a brief assessment of the groups, what went right, and what went wrong.

- The Barefoot Running-Related Groups: These groups were specific to the niche of barefoot running. They were great for learning and teaching about barefoot running, and even running in general. They were kinda good for learning about lifestyle stuff, like minimalist living. Ultimately, though, the limited topical specialization limited their usefulness for personal growth. And, quite honestly, I eventually got tired of the barefoot running fanatics and snake oil salespeople who preyed on the fanatics.

- The Hobby Joggas: This was my social running group from Michigan. They were (and still are) awesome, as a training group who pushed each other, as a collection of friends who helped each other run ultramarathons, and as a fun social group to hang out with wen we weren't running. The biggest problem? They were specific to West Michigan. Once I moved, I lost them.

- BRUCrew: This was a short-lived in-person and online group set up for functional fitness workouts and for "social challenges." The idea was to help members get fit and do social interactions that scared us, which would help us overcome social anxiety and introversion. It actually worked well (especially the online version), but lost steam as I got distracted with other projects.

- Fight Club: This was my mma gym in San Diego where I learned to fight. I was merely a student here, though I did progress into a bit of a leadership role eventually. I loved Fight Club; my coaches and teammates were awesome folks who, for the first time in my life, gave me a feeling like I wasn't an outsider. These were my people. Even though I've been gone for almost five years, I still train under my coaches. The problem with Fight Club is the same problem as The Hobby Joggas... once I moved, I lost them.

- Man Camp: Man Camp was the first real "Gang of Men" I intentionally started. Originally, it existed as a Facebook group and a blog. Eventually, I re-wrote the original blog (this blog you're reading right now) to make it a little less offense. Man Camp was based on the idea of fixing guys who fit the mold of Nice Guys, and was intended to fix bad, sexless relationships and teach men about the nature of women. One of my academic backgrounds was the psychology of sex and gender, so this is an area of relative expertise. For the right kinds of men, this group was extremely successful. It had two problems, though - it was online-only and it was pretty limited to fixing sex and relationship issues. Its mission limited its usefulness to help men get better at being men outside of that narrow focus. It did bring together a group of the kind of men I want in my corner. Several of this group's members will likely play a role in any new "Gang of Men' project that I develop.

- Cotton Underwear Nougat Troupe: This was another kinda goofy short-lived online project that was supposed to bring men and women together to talk about sex and relationship issues. It ultimately failed because too many of the women who participated were new age hippies who were really life coaching (which is a bullshit industry filled with amoral grifters) and a too many men who were the "Nice Guys" I had tried to fix with Man Camp... but were militantly opposed to changing. The lone bright spot from this group came from having the opportunity for me to convince a... more mature... female friend to take the advice I gave in this tuber-controversial blog post to find a genuinely good man, for whom she eventually married.

- El Diablo Combatives: This was my jiu jitsu and mma gym in Colorado. It was an attempt to re-create Fight Club. It ultimately failed because being a gym owner sucked. Aside from being bad at running the gym, I also wasn't willing to lower the standards of the students we would accept to pay the bills. It did, however, result in...

- The Lab: The Lab was a bit of a social engineering project that developed because I had some folks at my gym who are really awesome people who shared a lot of my goofy Utopia ideas. We had a Facebook group and a blog, but we also met a few times in-person. The general idea as the creation of a Tribe of like-minded people who would help each other grow and provide support for each other. The idea was best summarized in this blog post here on this blog. Ultimately, I made three mistakes. First, the Lab was part of my gym, which was in the process of failing. Don't build castles in swamps. Second, the project was really ambitious, and none of the key players had the time or resources to get the project off the ground. Making things overly complex is both a blessing and a curse... in this case it was more of the latter. Third, I experiment too much to lead a project that requires a lot of focus. I like continuously tweaking my ideas, which makes it really difficult to build big projects from start to finish. The confluence of those three factors spelled doom for the project, though I still dream of making it happen one of these days.

So that's a summary of the social groups I've been a part of over the years. I threw all of these ideas into a giant Vitamix, hit the puree button, and got...

IV. The New Gang

Earlier, I stated my explicit goal:

The ultimate goal is to surround myself with a "gang" other men who

have a strong desire to improve themselves in a variety of fun, exciting, adventurous ways, have a

strong sense of duty to provide and protect their families and communities, and

also crave the camaraderie and brotherhood of other men who are striving for the same.

Basically, I'm working to create an updated version of "Man Camp" with all the lessons from my other experiences AND with an explicit focus on doing cool shit. Our world isn't especially friendly to masculinity these days, and there's a better than average chance we're going to need masculine men if my predictions about The Voiding are in any way accurate. We have real need for men to have the opportunity to learn how to be better men, and have the opportunity to prove themselves to other men they respect.

Like I stated in the original quote at the beginning of this post, this process would be A LOT easier if our world were clearly falling apart. If we were cold, starving, and living in constant fear, it would be wayyy easier to organize a gang. But we're not there. Yet. I might be totally wrong about my dire prediction about The Voiding. But I'd rather start building a gang today instead of waiting for the grocery shelves to empty and the lights go out.

Anyway, for those of you who enjoy reading, this idea isn't mine. It's merely a synthesis of a lot of other ideas. The ideas that form the crux of my proposed Gang of Men come from these folks and their works:

- Jack Donovan ("The Way of Men" and "Becoming a Barbarian"),

- Jocko Willinck ("Extreme Ownership"),

- Sebastian Junger ("Tribe"),

- Mark Manson ("The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck"),

- Rollo Tomassi ("The Rational Male"),

- Leil Lowndes )"How to Talk to Anybody")

- Tucker Max and Jeffrey Miller ("What Women Want"),

- Sam Sheridan ("The Fighter's Heart),

- Dave Grossman ("On Killing" and "On Combat"), and

- Gavin de Becker ("The Gift of Fear".)

... among others. There are a lot of people smarter than me who have a lot of phenomenal ideas about the nature of masculinity, how society is vilifying those of us who crave what our grandfathers enjoyed, and long to get back to our primal roots where men and brotherhood were one in the same.

For the last six months, I've been toiling away behind the scenes, playing with ideas and working out logistics. I've built a complex, intricate plan, then distilled it down to its simplest elements. Build more complexity, then do more distilling. Five or six such cycles later, I finally have a plan for the Gang of Men.

To really be effective, I needed to add some elements. The most important aspect was defining the exact type of man the group is designed for, which are men who love doing "guy shit", long for brotherhood, have a strong desire to provide and protect for those they love, and have strong ethics. The type of men I'm looking for are the men who look around at other men today and feel a sense of disgust at their weakness. Or, as was the case for myself not too many years ago, you feel that disgust when you look in the mirror.

The group also needed an identity, which included a unique name. The group needed a clear focus. The group also needed a clearly defined set of values and an accompanying ethical code. The group also needed an aspect of gamification and other creative elements to leverage the psychology of motivation and play. There were other elements that had to be added, which I'll detail in future posts.

I also needed to eliminate some elements. Most importantly, I needed to be careful to exclude the kind of men we don't want. As I learned from the Man Camp experiment, not every man wants to improve, not every man wants to make a commitment to a group, and not every man understands the concept of honor. I also needed to eliminate the structural complexity, especially in the beginning. Finally, I needed to eliminate the hyper focus on relationships. While the new Gang of Men will feature a lot of my teaching on improving relationships, understanding women, becoming more attractive, and other such topics, the main focus is helping each other get better at being men.

I'll be sharing the details in future posts in the very near future, but here's a preview for The Valorians.

We are The Valorians, a brotherhood of modern men forged in the fires of adversity, bound together by a shared commitment to excellence, and driven by an unrelenting hunger for success. Our mission is simple yet profound: to elevate men to their highest potential, to imbue them with a sense of purpose and direction, and to equip them with the tools and skills necessary to overcome any obstacle and conquer any challenge.

We stand for strength, courage, honor, and mastery, and we believe that these virtues are the keys to unlocking the true potential of every man. We reject the notion that modern men are weak, passive, or unfulfilled, and we refuse to accept mediocrity as the status quo. Instead, we choose to embrace the challenges of life head-on, to push ourselves beyond our limits, and to forge a new path that leads to greatness.

We are the embodiment of the warrior spirit, the guardians of tradition, and the pioneers of a new era of excellence among men. We are The Valorians, and we are dedicated to empowering men to reach new heights of success, fulfillment, and happiness. Join us on this journey, and together we will transform yourself and you into the man you are destined to become.

"Valorians" was chosen because valor is the defining characteristic of the men of this new Gang. "Valor" means displaying courage in the face of danger. This is a literal virtue this new Gang will work to instill, but it's also something we will instill in a more figurative sense. Embarking on a journey of self-improvement AND doing so in the presence of other men is scary shit and requires valor. Ergo the name.

Anyway, I'll be sharing more in the near future. If the idea resonates with you, stay tuned.

~Jason

***